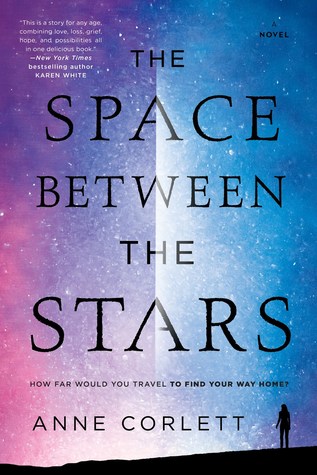

The Space Between the Stars

The Space Between the StarsAuthor: Anne Corlett

Genre: Science Fiction/Dystopia

Release Date: February 6, 2018 (paperback)

Publisher: Berkley

Description:

In a breathtakingly vivid and emotionally gripping debut novel, one woman must confront the emptiness in the universe—and in her own heart—when a devastating virus reduces most of humanity to dust and memories.

All Jamie Allenby ever wanted was space. Even though she wasn’t forced to emigrate from Earth, she willingly left the overpopulated, claustrophobic planet. And when a long relationship devolved into silence and suffocating sadness, she found work on a frontier world on the edges of civilization. Then the virus hit...

Now Jamie finds herself dreadfully alone, with all that’s left of the dead. Until a garbled message from Earth gives her hope that someone from her past might still be alive.

Soon Jamie finds other survivors, and their ragtag group will travel through the vast reaches of space, drawn to the promise of a new beginning on Earth. But their dream will pit them against those desperately clinging to the old ways. And Jamie’s own journey home will help her close the distance between who she has become and who she is meant to be...

Praise for THE SPACE BETWEEN STARS:

“Strikingly written, with very human characters and a deep concern with human frailty...an excellent debut.”—Tor.com

“Corlett offers a thoughtful examination of how individuals find meaning and fulfillment in the face of an apocalyptic event then wraps up with a thrilleresque ending.”—Booklist

“With its unique plot and luminous prose, it’s hard to believe that The Space Between the Stars is a debut novel. Anne Corlett understands the complexities and frailties of the human heart and captures it brilliantly on the page. Don’t let the setting fool you—this is a story for any age, combining love, loss, grief, hope, and possibilities all in one delicious book. Definitely one for my keeper shelf.”—Karen White, New York Times bestselling author of The Night the Lights Went Out

Chapter One

She knew it was the third day when she woke. Even in the twists and tangles of the fever, her sense of time had remained unbroken. More than unbroken. Whetted into a measure of such devastating accuracy that she’d wanted nothing more than to die quickly and be done with that merciless deathwatch count of her last hours. And dying was quicker, according to the infomercials that spiraled out from the central planets when the virus first took hold there. Most people were gone by halfway through the second day. If you were still lingering beyond that midpoint, chances were you’d still be there after the fever had burned itself out in a last vicious surge on the third day.

Jamie could taste blood in her mouth, bitter as old coins, and her back was aching with a dull, bed-bound creak of pain. But her bones were no longer splintering in some unseen vise, and there was none of the spiraling vertigo that had flung her about inside relentless nightmares. In the throes of the fever, skeletal horses had leered at her, and an organ-grinder who was nothing but teeth and hands had turned the handle faster and faster until it all blurred into nothingness.

Her senses were slowly coming back online. She could hear her own ragged, uneven breathing, and she could smell the reek of sweat-stained sheets.

She was alive. That realization brought no leap of joy or relief. There was a nag of unease working its way around the edges of her thoughts.

Survival was something she’d never dared hope for in those interminable days before the virus took hold on Soltaire, when there’d been nothing to do but wait for the inevitable to hit their planet too. The disease’s long incubation period meant that it had already reached every corner of settled space before the first symptoms appeared on the capital, Alegria. The messages from Alegria and the central worlds stopped a week or so before the sickness hit Soltaire. The infomercials had already given way to blunt emergency transmissions. As the days passed, the silences between them grew longer, the messages shorter, less coherent, as though the airwaves were fraying. But by then they knew what was coming. The virus was terminal in almost all cases.

Ninety-nine point nine nine nine nine percent, one of the ranch hands had said. Jamie didn’t know where he’d gotten that figure, but it spread and became fact. That was the day they all stopped looking at each other. How many of them could hope to make it into a minority so staggeringly small? The odds were akin to launching a paper airplane off the planet’s surface and hoping to hit a target back on Earth.

Zero point zero zero zero one percent.

She felt stiff and brittle, like she’d snap if she moved. Her senses had turned on her. She could hear all the noises that her home wasn’t making. The generator at the main house was temperamental, and it wasn’t unusual for it not to be running. But she should have been able to hear the distant hum of machinery from the logging station over at the lake, or the farmhands calling to one another and swearing at the cattle. Instead, all she could hear was the soft, barely-there swish of the station’s turbine and the squabbling of the immigrant sparrows in the trees behind the cabin.

That was it. No human sound.

Survival was a one-in-a-million chance. The virus was a near-perfect killing machine. Contagious as hell, it had a vicious little sting in its tail. It mutated with every reinfection. A single exposure was survivable—with luck—but it was as though it knew humans. As the disease spread, people did what people always do. They clung and grabbed and mauled one another. They lined up at the hospitals. They died in the waiting rooms. They clutched at their lovers and held on to their children. And the disease rampaged joyously, burning through thought and will, then flesh, and, at the very last, through bone—until there was nothing but dust, and no one left to mourn over it.

Dust to dust, Jamie thought, rising slowly onto one elbow. The sun was slanting under the top edge of the window, illuminating the interior of the single-roomed cabin that had been her home for the last three months. It was a standard settler’s dwelling, flat-packed as part of some colonist family’s baggage allowance when the first ships made their way through the void.

Jamie’s head was aching, and her mouth was so dry that she might as well have been dust herself.

Had she breathed them in? The dead? Were they inside her now, clinging to her throat, hoping for some chance word that might carry them back to an echo of life?

Ninety-nine point nine nine nine nine percent.

She yanked herself back from the fall that lay beyond that thought. It might be different here. They’d had some warning. And they didn’t live crushed up close against each other, like on the central worlds.

But . . . the silence.

Something snagged in her throat, and she coughed, and then retched, doubling over.

Water.

The thought instantly became an urgent need, with enough force to tip her over the edge of the bed and into a sprawled half crouch on the stone floor. She pushed herself upright, leaning hard on the bed, and then crossed the floor, moving with a clubfooted awkwardness. When she reached the sink, she clung to it with both hands. The mirror in front of her was clouded and warped. The distortion had always unsettled her, with the way it caught her features and twisted them if she turned too quickly. But today the clouded surface was a relief. She didn’t need a reflection to know how reduced she was. She felt shrunken, stretched too tight over her bones, her dark hair hanging lank and lifeless on her shoulders, her olive skin bleached to a sallow hue.

The tap sputtered, kicking out a little spurt that grew into a steady stream. She splashed at her face, the cold water forcing the shadows back to the edges of her mind, leaving nothing to hide that pitiless statistic.

Ninety-nine point nine nine nine nine percent dead.

Ten billion people scattered across space.

Zero point zero zero zero one percent of ten billion.

Ten thousand people should have survived.

Spread across how many populated worlds? Three hundred, or thereabouts. Thirty-three survivors per world. And a bit left over.

But she had a nagging sense that her math was wrong. But then she was weak, reduced by her illness.

It was making it hard to think clearly.

When the answer struck her, she initially felt only a little snick of satisfaction at figuring it out. All worlds were not created equal. Almost half the total human population lived on Earth and the capital planet cluster. There must be a couple of billion people on Alegria alone.

That meant two thousand survivors. Set against the ominous silence outside the cabin, that felt like a vast number, and she felt a flicker of relief.

But then there were all the fledgling colonies, right out on the edges of civilization, some of them numbering only a few hundred people.

Soltaire fell somewhere between those two extremes. Its single landmass was sizable enough—about the size of Russia, she’d been told—but settlement had been slow. There were ten thousand people, or thereabouts, most of them clustered around the port, or over in Laketown. Then a few smaller townsteads, and a clutch of smallholdings, as well as the two main cattle breeding centers, at Gratton Ridge and here at Calgarth.

Ten thousand people.

All the heat seemed to drain out of her body.

Zero point zero one.

Not even a whole person. There shouldn’t have been enough of her left to do the math.

A cramp stabbed through her stomach and up into the space beneath her ribs, doubling her over.

Breathe.

It was just an estimate. Maybe other people had done what she’d done, and locked themselves away the second they’d felt that first itch in their throat. But then it hadn’t been hard for her to follow the emergency advice. There was no one depending on her, no one wanting her close. But if she’d still been with Daniel, would one of them have given in and crawled to the other, seeking warmth and comfort and the reassurance of another heart beating near theirs?

Daniel.

His name slammed into her, and she put her hands to her head, waiting for the reverberations of that thought to stop, so that she could start feeling something.

Nothing.

Daniel, she thought, more deliberately this time. The man with whom she’d spent the last thirteen years. The man she’d loved.

Still loved.

Maybe.

No.

That was a distraction she didn’t need right now.

She stood up straight, moving slowly and carefully as though the air might shatter at an incautious movement, and reached for the towel hanging beside the sink. It was a threadbare rag of a thing that looked as if it had been here since the first settlers, but towels were just one of the things she’d forgotten when she left Alegria. She’d arrived with just a handful of clothes and essentials, plus a few personal bits and pieces. Daniel had taken it as a good sign. Your stuff is all where you left it, he’d told her, in one of his mails. Whenever you want it.

Whenever you want me. That was what he’d really been saying.

I want you now.

The thought caught her by surprise. She’d turned that question over and over in her mind since she’d been out here, in an endless inverted he loves me, he loves me not. She’d analyzed every memory, replayed every argument, every tender moment, and she’d come up with a different answer every time.

Clearly she’d needed to wait until the world had ended before deciding that she did love him.

Loved him, wanted him. It was the same thing, wasn’t it? A pull, a stretching of the tether that started with the other person and ended somewhere deep in your chest. She’d felt that tug when they’d talked on the long-distance airwave at the port. When was that? Three weeks ago? The conversation was stilted and artificial. Even though he’d shuttled out to the capital cluster’s long-range station, the time delay was so marked that while she was speaking, the mouth of his crackled doppelgänger was still moving to the echo of his last remark, as though he were talking over her. He was going to Earth for a few weeks, he told her.

Work. He just wanted her to know. In case...

That in case had been left hanging between them. That was when she felt that tug. It wasn’t strong enough to make her say what she knew he hoped she’d say. But when he asked if they could talk again when he got back, she agreed. She’d even found a smile for him as they said good-bye, although it hadn’t quite felt like it fitted, and she didn’t know if he’d seen it before the connection was severed.

He’d been heading for Earth.

Four billion people on Earth. Four thousand survivors.

What were the chances of them both making it? She felt suddenly weak and couldn’t work it out. Panic was starting to swirl up inside her chest.

Breathe.

She walked over to the cupboard. Underwear, a pair of jeans. She pulled them on. No T-shirts.

The clothesline. She’d been hanging out laundry when the first spasms had sent her to her knees, and then, by slow increments, to the medicine drawer.

She stood still. Until she went outside, this could all just be a game of what if?

Zero point zero zero zero one.

“Shut up.” Her voice sounded thin and rusty, and she swore, another harsh scrape of sound, then opened the door.

The sun was high overhead, the sky its usual denim blue, fading to smoky marl at the horizon. Outside the cabin a half line of laundry swayed in the breeze. At one end, a bedsheet trailed from a single peg, the line sagging under its weight. The laundry basket was on its side, her clothes streaked and crumpled in the dirt.

She realized she’d instinctively wrapped the towel around her before stepping outside, just as though one of the farmhands might wander by with a casual wolf whistle.

Little things, she thought. It was too easy to forget, to fall back into past habits, paying too much attention to all the tiny, insignificant things.

She kept the towel clamped against her sides until she’d unpegged a gray T-shirt and pulled it over her head. Her boots were abandoned by the door, as usual, and she sat to lace them up.

The birds had scattered over to the boundary fence, their quarrel muted by distance. The turbine turned quietly, and the cattle grumbled from the barn. She stood up, stretching her cramped limbs, forcing herself to look around. The main house was still and silent and she turned away, toward the open land beyond the station fences. A couple of faint scraps of cloud drifted over the hills, carrying a vague promise of rain.

Her thoughts were spiraling out, beyond the simple fact of the warm breeze and clear sun. This world had long growing seasons, regular rainfall, a simple infrastructure. It would be an easy enough place to survive, if surviving became all there was.

No.

The door of the main house was closed, but the curtains were open. Someone could be looking out right now. Or perhaps someone had heard her. Maybe they were stumbling to the window right now.

But she didn’t move.

There was a rumble from the barn. If the Calgarth herd had been milkers, they’d have been protesting their swollen neglect long and loud. But these were breeders, and their complaints were probably focused on being barn-bound and out of feed. If those basic needs were met, they wouldn’t be troubled by the decimation of the human world.

She turned away from those empty windows and walked down to the barn, swinging back the bar that kept the cattle from the yard. She found the herd outside, gathered in the shade of the back wall, near a trough of greenish water and a pile of fodder spilled from an upended bin. The scattered feed spoke of someone using their last strength to make sure the herd had enough to last until . . . for a while.

Her heart felt small and hard, as if her illness had turned it into something other than flesh. She hadn’t spent much time with Jim Cranwell, who ran the farm, despite being his resident veterinarian, but he’d always been courteous. She’d had more to do with his grandchildren, who’d run in and out of the barn, clambering between stalls and treating the cattle like oversized pets. At first she’d wished they would leave her alone. She found their constant questions distracting, and she veered between patronizing, oversimplified answers and curt, too-adult responses. But she’d gotten used to their presence, even playing the odd game with them, although she always tired of it before they did.

She’d have to go around the station and prop all the gates open. There was a stream near the boundary fence, so they’d have water. She wasn’t sure what to do about the bulls. If she left them roaming free they’d fight, but if she kept them separate, there’d be no new calves. What happened when there was no prospect of anything beyond this generation? What happened when . . .

She gripped the edge of the door frame, her breath growing ragged. There’d be other people who’d beaten the odds. She had to find them. Until she did, these thoughts would keep piling up until she was crushed beneath them.

She stood for a moment, breathing slowly, trying to think about nothing but the blue of the sky and the curve of the hills. Then she turned and walked, slowly and heavily, toward the silent house. Anne Corlett is a criminal lawyer by profession and has recently completed an M.A. in creative writing at Bath Spa University. Her work has been published in magazines and anthologies, and her short fiction has won, placed, or been short-listed in national and international awards. The Space Between the Stars is her first novel. Visit her online at AnneCorlett.co.uk and Facebook.com/Anne.Corlett.

No comments:

Post a Comment